My week in the workshop

Exploring storytelling in a real-world setting

Leaving the car at home, I hop on a Welsh train to a city I don’t like to attend a multi-day semi-experimental workshop that throws me into various activities with 10 strangers. It’s an odd mix of cognitive behavioral therapy, life coaching, authenticity and mindfulness training, and bonding through shared revelations and experiences. It feels like Alcoholics Anonymous, group therapy or a cult indoctrination rite, and it’s not the sort of thing I’d normally do because I don’t live in California or have a septum ring. By 10.30am on the first day, three people have cried and one has run out of the room. I consider defecating myself but decide not to.

We do lots of exercises designed to increase trust and help us get to know each other. It feels like being on Big Brother or The Traitors, except everyone is white and we don’t have to nominate or murder each other. No-one is allowed to use their phone. Three successive people come out as gay, which strengthens my resolve not to. We’re supposed to be representing our core values, and I realise I’m being my truest self not by going “I’m gay!” but by letting people judge me for who I am without labels getting in the way. Societal pressure to come out is just as bad now as societal pressure not to come out used to be decades ago, and my ambivalent relationship to everything “LGBTQIA*+” isn’t something I need to get over - it’s borne out of principle and a wariness of cult dynamics. If I had a long-term partner, I think it would be different; perhaps I’d be proudly regaling how Wolfgang and I had just bought a house and adopted 9 Malawian orphans and a bichon frise. But I’m not going to talk about being gay when I’m terrible at it and when the room is full of woke women. Some of the straight people mention their husbands or wives, but a few others like me don’t discuss their romantic lives in front of the group. Afterwards I find out accidentally that one of the older women has a famous husband. She didn’t mention it throughout the entire workshop, probably because she wanted to be there on her own terms and seen for who she was.

A nervous HR manager gets up on stage and tells us how she’s always dreamed of visiting Iceland. I’m desperate to take the mic next and say “I’d love to go to Iceland too, cos then I could get 10 pork sausages for two quid.” I bite my tongue.

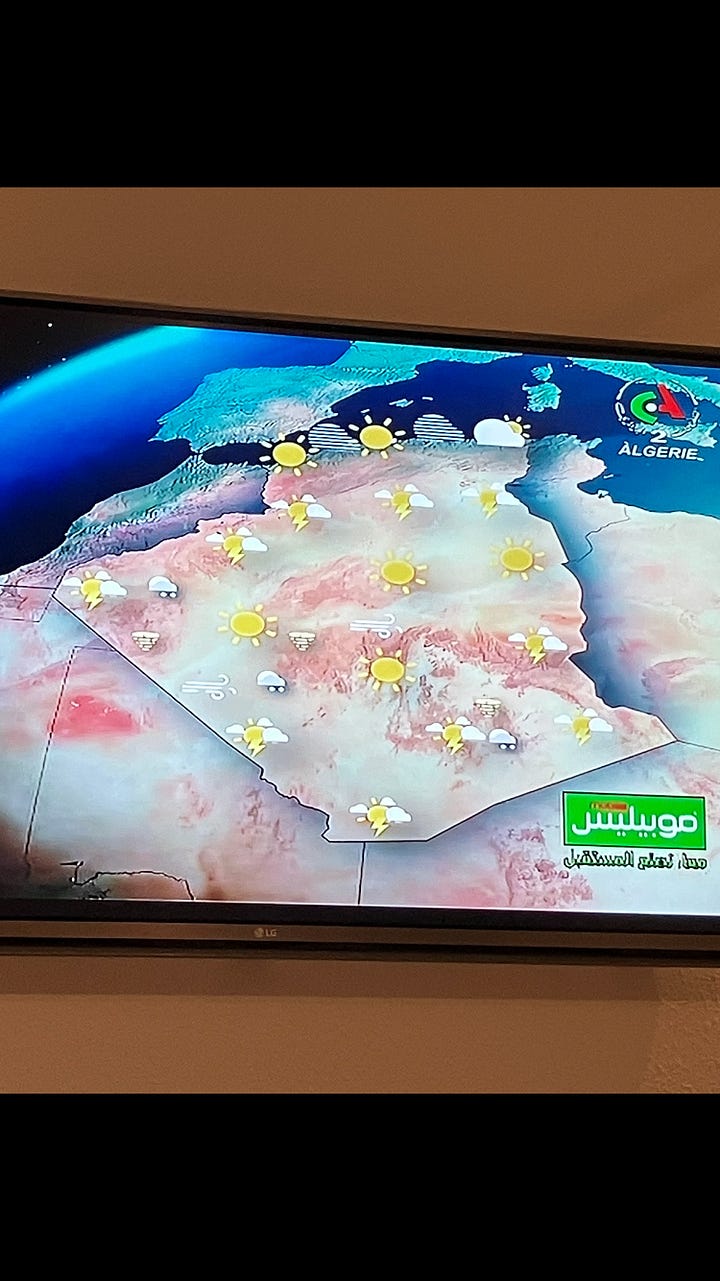

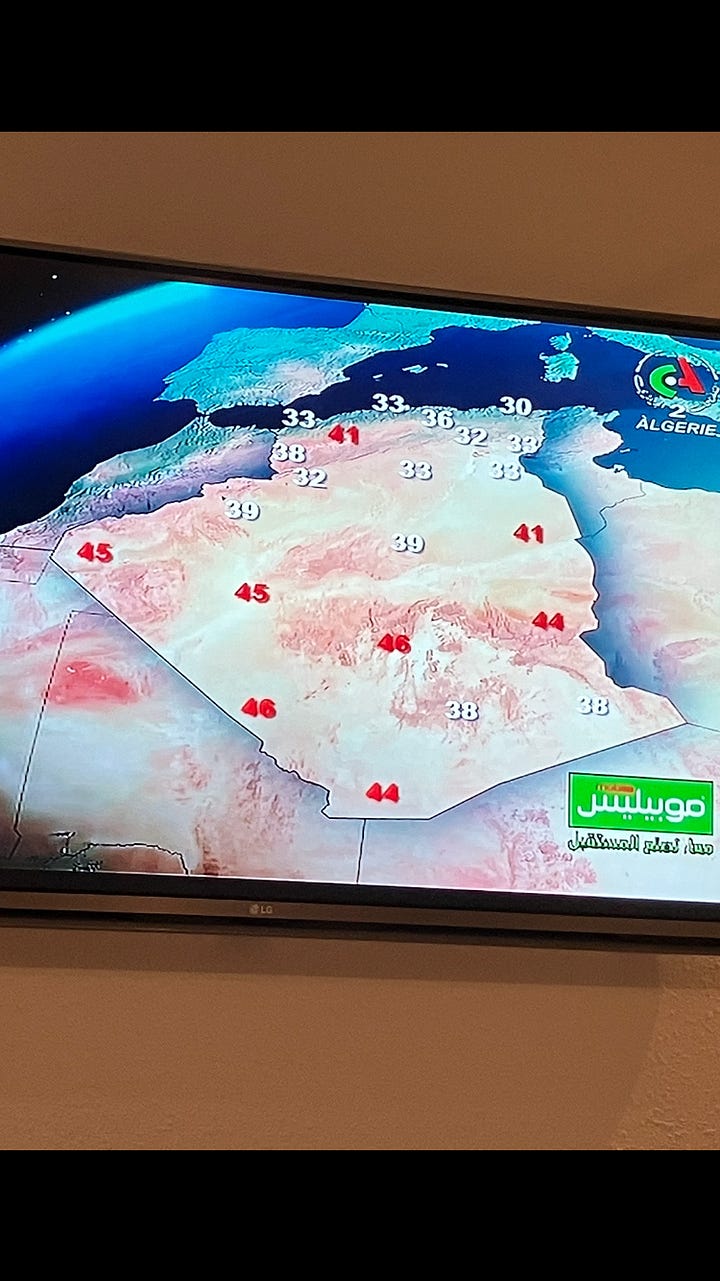

It’s intense and challenging, but I feel I’m growing. In the evening, my friend is too ill to make our dinner appointment, so I eat alone then head back to the hotel and mindlessly watch Algerian television on channel nine-hundred-and-something. The evening news seems to mostly consist of various military parades and official pronouncements. I wonder what it’s like living in a large authoritarian country - not one of the terrifying, extreme ones like North Korea or Eritrea, or a lawless state like Somalia or Haiti, but somewhere relatively safe and boring that people never really think about, like Algeria or Tanzania. “I’d have to be married,” I think. I’d almost certainly have kids. Or I’d have tried to leave for Europe and ended up being sold into indentured labor on a tomato farm in Almeria. Hey, free food.

On the second and third days, we continue the work. A different person runs out of the room in a panic; the trainer goes to look for her and fetch her back. She said she needed to “get some air” but I think she went to Greggs. By this time, half of the group has been crying at one point or another. There’s more snot and tears than the average episode of Star Trek: Discovery. A young activist takes to the stage and talks about how she campaigns in her workplace for “everyone to use the toilet they’re most comfortable with”. I bite my tongue again; I don’t want to say anything about women’s sex-based rights when I’m one of the only men in the room. Later, someone asks the activist what her plans for the weekend are, and she answers “My girlfriend and I are going to go to the park and be gay!” (“That’s so embarrassing,” my youngest gender-critical friend says when I tell her afterwards.)

The final day is extraordinary. By this time, I’ve gravitated into a subgroup with the two other men and a female scientist. She’s brilliant - clearly the youngest participant, though she never mentions her age - and I totally see why she’d rather hang out with the three guys than the millennial and Gen Z women. I listen to her talk beautifully about protein transcription, Italy, and missing her dead cats. She reminds me of an American girl I bumped into at Venice Mestre station in 2021, who told me that she felt more at home in Florence after 6 months than she did in her entire life until then. I asked what was the one thing she missed from back home, and she showed me an Arizona sunset on her broken phone screen.

One of the straight guys announces to the group that he and I have a “bromance”. The trainer says she can see a “love” between us. I’m happy he feels comfortable with me but I’m always surprised when this happens. “Men find it difficult to have friendships,” the trainer says. I think there’s truth in that, but I always underestimate how hard it is for straight men, even those who seem outwardly content and sorted. They put more walls up with each other, even when they’re literally putting walls up.

On stage, I bare my soul. I talk about growing up in a hoarder house, living abroad, and some of the biggest mistakes I made in my career - both the ones I handled well and the ones I didn’t. I discuss looking after my parents and trying to facilitate fun, memorable experiences for other people and make their lives easier. “If I’m in a store and I can help an old person use a touchscreen ordering system or assist my neighbour with his iPad, that’s a good day for me.” I love being people’s tech support. I mention an autistic friend who visited me in Germany once for a few days. “He’d never been abroad by himself before, he’s quite hyperactive, and at times I felt annoyed at him and found him hard work - but at the end, when he said ‘I’ve had a fantastic time, thanks for looking after me’, that made it all worthwhile.” Especially when he was still telling people about the trip years later. That made me proud.

Afterwards, people ask for my Instagram. “I don’t have any social media,” I say. Referencing my hoarder story, someone then asks for the number of my rotary phone instead. I feel love for these people. As I’m packing my bag, the two straight guys come over and tell me that I’m an amazing storyteller, I don’t know how funny I am, and they’re in awe of how I connect things and structure my stories. I’m humbled, and say that I think it comes from writing. Storytelling in person isn’t so different from storytelling in an article, it seems.

It takes me the full four days to realise how safe I make other people feel. But I can never quite get my head around how differently straight men and gay men respond to me. On the whole, gay men don’t find me funny or interesting to talk to, or they find it hard themselves to keep the conversation going. We don’t gel or have a lot of overlaps, and I have 15 years of evidence of this; they might think I look good, but I rarely get positive feedback on any aspect of my personality. Yet straight (and bi) men think I’m brilliant because they see me as a whole person, not just a body. Even back in the 2010s when I wrote a series of articles about gay culture in eastern Europe that went viral and was read by tens of thousands of people, most of the positive responses were from women and straight men. The people who booked me for more writing work or conference appearances off the back of those articles were women and straight men.

On my last night in Germany before I moved back to the UK, a straight acquaintance told me “Your words have power. I still remember our first conversation six years ago, man. You should be a politician or an entertainer.” All we had talked about back then was digital audio workstations. But it meant something to him, and he remembered it. No gay man has ever responded to me like that. Another guy at a party, who I only ever met once, said to my friend Michael afterwards that I was the only person who’d made the effort to talk to him all evening. From my perspective, I was just making casual conversation while Michael was away getting drinks at the bar. But he felt listened to. To be interesting, you have to be interested. My gruff, very heterosexual driving instructor used to look forward to our lessons every single week because I made him laugh, he loved hearing my stories and he could vent about his divorce.

There’s a line in Mrs Doubtfire that I’ve always resonated with - “personally I prefer short, furry and funny”. I’ve come to realise that being short, furry and funny is a superpower. Like Robin Williams or Charlie Day, you have a tremendous ability to put others at ease, engender trust, and exude warmth, collegiality and curiosity. Zelensky is the GOAT of short, furry and funny, and he’s one of the most admired people on the planet. I realise now that the mystery isn’t why straight men like me - it’s why gay men don’t. And I don’t think the problem lies with me.

My bromance partner takes the bus part of the way back with me, talking animatedly the whole time, before our paths diverge. “See you soon!” he says hopefully, almost willing me to not leave. In the station, I walk past a Progress Pride flag and a wall of “Pride Planters” overflowing with flowers in rainbow colours. An accompanying poster says something about “feeling seen”. I don’t, except by the CCTV. I check my phone. A gorgeous, intelligent, age-appropriate guy I went on a date with a week ago has messaged me back. He “didn’t feel a spark”.

Add the Filipin@ woman LARPing as "LGBTQIADAP+++," and you've nailed my grad school vibe.